Transport, mobility and congestion continue to be hotly debated topics in politics, the media, academia and soon at the Urban Motion conference in Brisbane. And rightly so, writes Marcus Foth of Queensland University of Technology

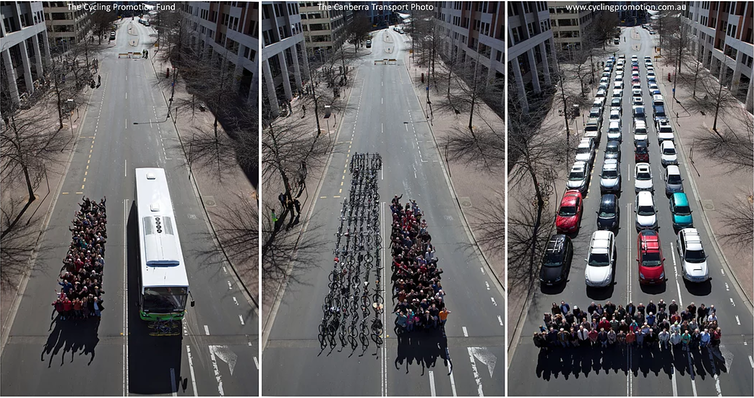

Most transport resources are being used inefficiently. The Canberra Transport Photo shows the road space required to move 69 people using public transport, bicycles and private motor vehicles. Cycling Promotion Fund, CC BY

Transport, mobility and congestion continue to be hotly debated topics in politics, the media, academia and soon at the Urban Motion conference in Brisbane. And rightly so.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics counted 19.2 million registered motor vehicles in Australia as at January 31 2018. While the human population grew by 27% since the turn of the century, vehicle numbers increased by 43% and continue to grow in all states and territories.

The Australian House of Representatives Standing Committee on Infrastructure, Transport and Cities recently released a comprehensive report, Building Up & Moving Out, on its inquiry into the Australian government’s role in the development of cities. The committee recommends:

… the Australian Government, in conjunction with State and Territory Governments, undertake the development of transport networks which allow for fast transit between cities and regions, and within cities and regions, with a view to developing a more sustainable pattern of settlement based on the principle of accessibility at a local, regional and national level. The Committee further recommends that the development of a fast rail or high speed rail network connecting the principal urban centres along the east coast of Australia be given priority, with a view to opening up the surrounding regions to urban development.

The committee further recommends the 30-minute city, active transport and a more sustainable urban form (Recommendation 11).

Leading up to the report’s launch, many of the inquiry’s submissions and expert witness accounts stressed the need to arrest urban sprawl and heed well-established research advice. All levels of government often ignore this advice to appease voters, but more roads and more lanes make matters worse.

Transport research provides clear evidence that increasing road capacity is a shortsighted band-aid that increases car travel. It also promotes driving dependency and ultimately makes congestion worse.

Many of the report’s transport-related aspirations point in the right direction. Yet many of them are not new and come with their own set of challenges.

Proposals to solve Australia’s mobility crisis appear to be dominated by technocentric optimism – a strong belief that new technology and disruptive innovation will somehow make it all better. Contenders for the transport panacea include car-sharing and ride-sharing platforms, electric vehicles, autonomous vehicles, trackless trams and more efficient traffic flow systems enabled by smart city investments in IoT (Internet of Things) sensors, big data analytics and urban science. Let’s debunk some of this.

More disruption?

The notion of disruptive innovation is often believed to bring about change for the better. One of the most commonly mentioned examples is Uber and similar commercial ride-sharing platforms. They certainly disrupted the established taxi industry. But cabs are no longer their main competitor.

Uber launched the “Pool” feature, which optimises routes so more than one rider can share the same car. As a result, the cost per ride now competes with public transport rather than just cabs. And this risks making inner-city traffic worse.

More driverless cars?

Another often-cited disruptive innovation involves autonomous vehicles and driverless cars. While they may come with economic and environmental benefits, there are as yet unresolved issues.

For example, the ethics in AI can cost people’s lives, road usage funding and taxation are unclear, and the average car occupancy can drop below one. As a result, without regulatory intervention, self-driving cars will not reduce congestion but add traffic to the roads.

More efficiency?

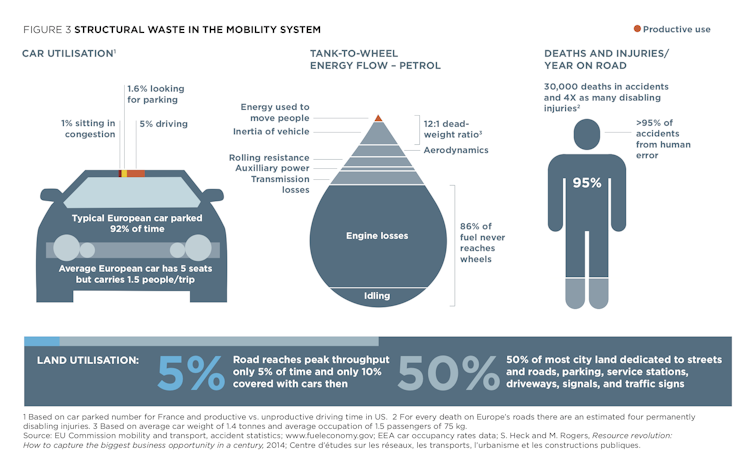

Transport offers vast room for improvement, so it is not surprising that optimisation is a low-hanging fruit. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation identified significant structural waste not only in fuel tank-to-wheel energy flow but also in road utilisation.

Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Growth Within: a circular economy vision for a competitive Europe, Author provided

Researchers at MIT and ETHZ propose a slot-based intersection that would double the usual capacity and herald the “death of the traffic light”.

These efficiency gains are welcome. Yet, considering the ever-increasing demand for mobility, these measures on their own will not solve our mobility crisis.

Wanted: leadership!

What is seldom questioned is the need to travel in the first place. The right to mobility and freedom to move locally and globally are undoubted. But it is worth asking what regulatory instruments and economic shifts can produce sustainable mobility.

Some examples that have started making their way into the mobility debate include the impact of nomadic work practices on transport demand and distributed co-working spaces to reduce the need for CBD commutes.

Progressive policy interventions, such as road congestion charges and free public transport, lack the backing of political leadership in Australia.

Longer term, there is an urgent need to seriously consider even bolder policy innovation. We can learn from overseas examples, such as the six-hour work day, the four-day work week and the slow city movement, which is more about slowing down the “hamster wheel” of life than traffic. We should also evaluate new approaches to human settlement as well as what impact universal basic income or universal basic services can have on reducing traffic congestion.

There are opportunities to join this debate at the Urban Motion conference in Brisbane on November 19-20 2018. We also invite participants to support the Future Cities CRC bid recently shortlisted by the Australian government.

This article is based on the presentation “Smart Cities are Slow Cities” at the QUT Real World Conversation forum on August 2 2018.![]()

Marcus Foth, Professor of Urban Informatics, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.